JACKSONVILLE, Ala.—Late afternoon. I am in the deep woods. It is raining. I’m riding a tricycle along the Chief Ladiga Trail, pedaling toward Georgia with my wife. We are soaked to the gristle.

We are far from civilization. This trail cuts through ancient farmland, abandoned pastures, cornfields, peanut fields, and miles of kudzu-laden forest. We have twenty miles left to ride.

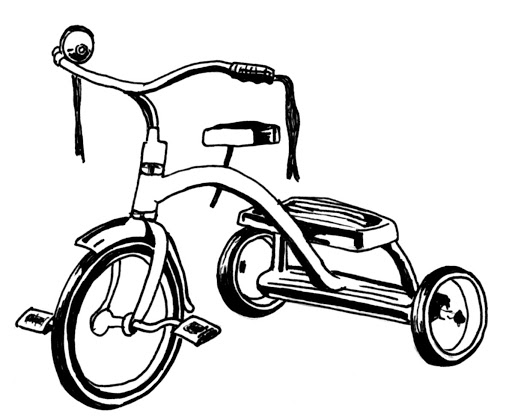

The tricycle I’m riding came from the classifieds. I bought it a month ago. The man selling it said the trike had belonged to his older brother who’d recently passed. His brother's name was Larry.

He said Larry had been excited when he bought this trike, he sorely missed cycling ever since his Parkinson’s disease made riding bikes impossible. Sadly, Larry never got to ride this trike more than a few times before he died.

When I first took this contraption for a test spin, the man nearly cried when he saw me ride it. He stood in his driveway, watching me pedal in circles.

He said, “Oh, Larry would be so happy to know

someone was enjoying his trike.”

When he’d finally gathered himself, he handed me a little red flag on a long pole.

“What’s this?” I asked.

He told me the flag attached to the back of the trike so that approaching eighteen-wheelers wouldn’t run me over in traffic. Then we laughed.

But as it turns out, the reflective flag is an important piece of safety equipment. The flagpole is about four feet tall and the flag flaps behind you when you ride, signalling to all oncoming traffic that you are an official member of the dork squad.

Right now my flag is flailing in the rain. I am not only a member of the dork squad, I am also the president.

But this trail couldn’t be more lovely. The Chief Ladiga Trail was once part of the Norfolk Southern Railway line. The winding flat paths…